|

History before Kazimierz

In 1241, unfortified Cracow had been invaded and plundered by the Tartars, who in a span of less than a hundred years, conquered the territories between Mongolia and Central Europe. They had burned buildings in Cracow, mostly wooden at that time. Only St. Andrews church built in stone, and the Wawel,, the princes’ dwelling, resisted the invasion. Several years later, in 1257, the Prince Boleslaw the Bashful gave the city the Location Act according to the Magdeburg Law. In contemporary terms, he announced the city as a free market zone, encouraging all possible investors to relocate to Cracow. All settlers were freed from taxes for the first fifteen years. The next laws instituted by Casimir the Great, very protective toward the city, gave Cracow a privileged position in the Kingdom of Poland for three hundred years. "Cracow Location Act" was also a collection of legal rights and responsibilities of its citizens, and it excluded the Princes, and afterwards, Kings, from its jurisdiction. During this period, the location acts of many other towns were instituted, which attracted many groups of settlers, mainly German and Jewish.

Today’s St. Anne Street in Cracow had the name of Jewish Street at that time, and was a seat of the Jewish diaspora. In the course of several years, Cracow had become the biggest and most powerful city in this part of Europe; a multicultural city populated by representatives of many European nations. The city was contained within its fortifications, which limited its growth. One of the main trade routes, so important to the city, was a route from Hungary and Russia connected with a route leading from the Wieliczka and Bochnia salt mines. All these routes crossed an island just beyond the Cracow city walls. It was inhabited by traders competing with the city. Within a short time, a settlement developed on the island. It was so significant that King Casimir the Great gave it township rights, and named it after himself. That is how Kazimierz was born. In spite of Cracow’s privileged position, Kazimierz was a serious competition for its trade. In order to increase its importance, Kazimierz merchants and craftsmen erected two big churches; of the Holy Ghost and St. Catherine’s. In the eastern part of Kazimierz, close to the old village of Bawol (Buffalo), King Casimir the Great intended to create a permanent seat for the University of Cracow, which had several temporary locations at that time. The construction, started in the area of today’s Szeroka Street, was halted by Casimir’s untimely death. During his reign, Casimir the Great was a man of strong temperament and a womanizer; he had several wives and concubines. One of them was Esther, a Jewish woman living in Lobzow, outside of the city limits, with whom he had two daughters (they remained in the Jewish community). The Jews considered Casimir their benefactor and protector. The truth is somewhat different. Casimir the Great treated his subjects equally within the existing laws, and made sure the Jewish population had also the rights accorded to other citizens. Money circulation was one of the most important factors in the country’s development. The Jews played an important role as bankers at that time. King Casimir the Great announced a law limiting the yearly interest issued by Jewish bankers to 108%. From today’s perspective, it was a huge amount, but in those times it was customary to sometimes charge several hundred percent interest. Because of that, and because Jews were known to quickly accrue great wealth, they were not liked by the city’s non Jewish population. Jewish traders were also known to often break the law, like in the cases of buying and selling stolen property or breaking guilds’ regulations. A large part of the Cracow population was of German origin and it maintained strong social and economic ties with Germany. Anti-Jewish waves reached Poland via Germany several times before the end of 15th century, resulting in appropriation of Jewish property and sometimes murder. The rulers of Poland and of Cracow condemned those actions and the guilty were even put to death, sometimes though, they evaded justice. The second part of the 15th century witnessed Cracow’s growing splendor and prosperity. As mentioned above, Jewish merchants were a serious competition for Polish traders (to which many German settlers were added over time). The development of the University of Cracow gave a pretext to eliminate some of the competition. Under pressure, the Jews were forced to sell their properties adjacent to the University around today’s St. Ann Street. For some time they occupied the area of the Szczepanski Plaza by St. Szczepan Church. Finally ,they were moved to Kazimierz, located 1200 meters from the main market.

In terms of social promotion, the Jews benefitted. The obtained their own laws, their own administration and an area much bigger than they had had previously. However, they lost economically. The town of Kazimierz as an entity did not have the same rights as Cracow, and the Jews were subjected to additional restrictions. Every cloud has its silver lining, though. Theoretically, they lost, but in practice, the Jewish Kazimierz became the center of the Jewish culture for the whole Poland, and emanated its influence far beyond the Polish borders. In a sense, the Jewish Kazimierz was for some time a world capital of the Jews. It admitted those who were banished from other countries during Counter reformation. It had synagogues, Jewish schools, printshops established. It was a hub of activity for many Jewish intellectuals. The Jews did not live only in Kazimierz. They also inhabited several neighboring villages and towns. Rich Jews, among them many royal bankers, together with rich Polish gentry and the royal court, had their own residences around Cracow.

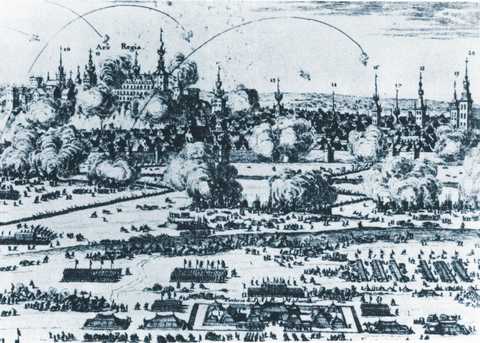

The time of the city’s growth was also the time of development for the Polish Jews. After the death of the last of the Jagiellonian dynasty, a free election was instituted. It meant the election of the king by gentry. Unfortunately, the majority of rulers of foreign origin ruined the country through their policies. The Saski dynasty played a particularly unforgiving role in that. In 1655 Poland and Cracow became a playing field for the Vasa dynasty.The Swedish ruler from the Vasa dynasty was fighting with a Polish ruler from the Vasa dynasty. As a result, the Polish towns, including Cracow and Kazimierz, lay in ruin.

After the Swedes occupied Cracow, the Jewish population collaborated with them. It was a mistake for which they had to pay for a long time. The Swedish troops leaving Cracow left a devastated and partially burnt city and destroyed suburbs. The immediate reconstruction of the city was in vain. A short time later there were other wars that affected it. As a result, Cracow lost its important economic and social role. For the next two hundred years the city barely survived.

Cracow’s weakness was reflected in the situation of the Kazimierz Jews.

The depopulated cities, including the Christian part of Kazimierz and Cracow became inhabited by the Jews. In the end of the 18th century, Poland had lost its independence. Cracow was occupied by the Austrians, who connected Kazimierz to Cracow in one administrative entity. To start, the Austrians gave the Jewish population an order to leave all their property and to move into the Jewish part of Kazimierz, thus practically introducing for the first time in Cracow the notion of a Jewish ghetto. This notion, even though it had a different connotation than the one from the WW2, was preserved until the thirties. It meant a social isolation of the Jews from the rest of the city. In the second half of the 19th century, the laws of Jewish isolation were abolished and the Jews started to expand into other parts of Cracow. Economically, the Jewish Kazimierz remained on the sidelines. The Jewish expansion found a reflection in the change of their mentality. They were adopting the Polish way of life and Polish cultural traditions, interpreting them in their own way. The Polish culture of the 20th century is brimming with the Jewish figures who contributed a great deal to it, of whom we are proud. It is not a Jewish culture. It is a Polish culture created by the Jews (just as the Marian Church in Cracow is a reflection of the Polish culture created, among other, by Germans.) Until the beginning of WW II, the main current of the Jewish culture was expressed in Yiddish and Hebrew. Every year there were several million newspaper issues in these languages. There were also Jewish movies and theater performances. The history of Kazimierz is a reminder about the tragic times. The Nazi plague had not been recognized as such right away by many states. The slogans of social justice pronounced by the fascists had many supporters. In the social and cultural realm nazism coincided with other cultural and social trends - on the one hand with futurism, on the other, it bore some resemblance to socialism. All that resulted in nationalism becoming popular in the thirties. The nationalist tendencies came to the fore in all Europe. Strong nationalism was also supported by the Jews. Polish nationalism had a milder face. When, in the thirties, the whole world turned away from the German Jews, only Poland accepted them. Other countries accepted only a few rich Jews bringing their property. Poland as the only country accepted a great number of poor Jewish population. Kazimierz became a seat of the Jewish refugees from Germany. From today’s perspective, the behavior of Jews in the face of Hitler’s aggression is incomprehensible. Many of them were convinced for a long time that nothing bad would come to them from the Germans That is why they did not try to leave. Unfortunately, war is the worst possible time. As the only European nation, Poland did not form a government collaborating with the Germans. As the only nation, they did not form the SS. Poland did not agree to invade Russia with Hitler, for which it paid a huge price. But even in Poland there were some traitors who collaborated with the Germans. When the Germans expelled the Jews to the ghetto in Podgorze, there were German collaborators looking for Jews hiding in Kazimierz. There were not many collaborators, but still some. After the war some of them worked with the Security forces and participated in numerous Security provocations, and giving false testimonies in political trials. Not many Jews returned to Kazimierz after the war. There were hardly any of them left and there was nothing to return to. Kazimierz became neglected and deteriorated fast. In the sixties the communist government tried to revive Kazimierz, and gave apartments there to the leading cultural figures at the newly built Szeroka Street. Many Polish celebrities lived there. At different periods some of the buildings of Kazimierz had been renovated, but since it was done superficially and they had no proper administration, the buildings deteriorated again after several years. The establishment of a cultural center on Jozefa 12 Street proved to be one of better ideas the communists had about Kazimierz. In the sixties and first half of the seventies, the cultural center was really a center of culture in Kazimierz. Many children living in Kazimierz were raised there, including the author of this article. In the last decade, there have been symptoms of Kazimierz revival in the intellectual and material sphere; a lot of work still needs to be done. The phenomenon of the Jewish Kazimierz is a phenomenon of ideas. The seat of the Cracow University that never happened there, became a seat of the Jewish cultural capital. It had its highs and its lows, together with Cracow. We owe great respect to this place because of our common history. tr. Joanna Schier Arthur Loboda

|